Developmental

Dysplasia of the Hip

DDH

This condition was once termed congenital dysplasia of the hip because it was thought that all these

problems began prior to birth. Recently, the term developmental dysplasia of the hip was coined because it was realized that some hips were normal at birth and gradually became dysplastic or malformed later.

This condition was once termed congenital dysplasia of the hip because it was thought that all these

problems began prior to birth. Recently, the term developmental dysplasia of the hip was coined because it was realized that some hips were normal at birth and gradually became dysplastic or malformed later.

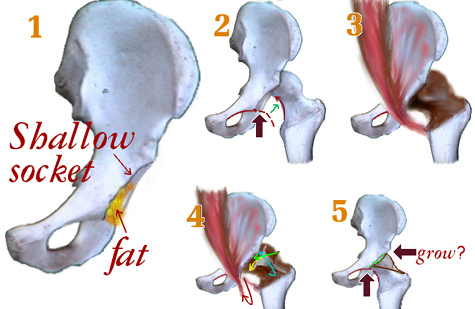

The hip is a ball and socket joint. The ball is the femoral head and the socket is the acetabulum. At birth, the femoral head and the acetabulum are made of mostly cartilage and are relatively soft. For the joint to form properly, the bone ends making up the joint must lie in proper orientation to each other. In hip dysplasia, this is not the case and abnormal forces are placed on the soft cartilage of the hip. The femoral head may be subluxed (partially out of alignment) or dislocated (completely out of alignment). The dislocated group can be divided into hips, which can be relocated, and those that cannot. The femoral head may also be in place but have abnormal movement within the joint termed instability. In each case, the hip will not grow properly causing increasing dysplasia with time.

Approximately, one in eighty hips present with some instability at birth. The number decreases to approximately one in one thousand hips at six weeks of age. At birth, circulating maternal hormones may make the ligaments about the hip a little loose, leading to the increase in instability. Sometimes as the maternal hormones are cleared from the infant's blood stream, the hip tightens up and is no longer unstable. True hip dysplasia is associated with females, first born children, the left hip, and a positive family history. A breech presentation is associated with a large percentage of dysplastic hips because the in utero position places abnormal stresses on the developing hip joint.

Early detection of hip dysplasia is important to limit malformation of the joint, while early treatment takes advantage of the hips ability to remodel and form properly. The hip examination is a standard part of a newborn examination. The primary care doctor will move the hips in an effort to detect instability. The doctor may describe the instability as a hip click, referring to the sensation of the femoral head moving in the socket. Not all clicks mean there is instability. Sometimes soft tissue passing over a bony prominence may produce a click and have nothing to due with instability. You really want to see if the femoral head is sliding over the edge of the acetabulum. This may better be defined as a hip clunk. If the femoral head does dislocate, it is important to know if it can be relocated or not. The hip is harder to treat if it can not be relocated.

The stability of the hip joint is best demonstrated using an ultrasound in the infant. The ultrasound can image the cartilage around the hip, which can not be seen in an infant on plain x-ray. Plain x-rays do not give a lot of information about the hip until the infant is approximately three months old. Also, an ultrasound can be performed, as the hip is moved better demonstrating instability. The person doing the ultrasound can watch the femoral head move in and out of the hip joint during the test. The ultrasound can also be done during the treatment to document improvement. After the age of six to eight months, ultrasound is not as effective for imaging the hip because too much of the hip is ossified and that obstructs the view of the ultrasound.

The treatment for hip dysplasia really depends on the age of the patient. The mainstay for treatment of children less than six months of age is the Pavlik  harness. The harness holds the hip in an abducted and

flexed position, which allows the best orientation between the femoral head and the acetabulum, allowing the hip joint to remodel and develop normally. The position looks like a

letter "M". It is worn full time for six to eight weeks until the hip has stabilized.

harness. The harness holds the hip in an abducted and

flexed position, which allows the best orientation between the femoral head and the acetabulum, allowing the hip joint to remodel and develop normally. The position looks like a

letter "M". It is worn full time for six to eight weeks until the hip has stabilized.

The harness has been very effective treating hip dysplasia. It is very well tolerated by the infant and is a very safe

treatment as long as it is properly placed and is adjusted as the infant grows. We see our children in the harness every two – three weeks to adjust the harness. If

the harness is not properly applied or becomes too tight complications could arise.

The child between six and twelve months of age may be too large to properly fit into a harness. In this

case, the child undergoes a closed reduction of the hip and is placed in a spica cast. This procedure is done in the operating room. The closed reduction refers to the physician manipulating the hip into a

relocated position guided by x-ray. Often, an arthrogram is performed at the same time. This involves injection of an x-ray visible fluid into the hip joint which when seen on x-ray defines the cartilage

surfaces of the joint. It helps the physician determine when the hip is reduced and how much instability is present.

If the hip has been dislocated for some time, the muscles around the hip shorten and become contracted. The hip adductors are often lengthened at the time of the closed reduction to take pressure off the hip

joint. The spica cast is worn for approximately three months. The position of the hip is checked periodically during that period to make sure it remains satisfactory. CT scans may be used to get 3-D

position information.

Once the child reaches about twelve months of age, their hip is difficult to reduce by closed means because the hip socket becomes filled with extraneous tissue and there is secondary contracture of surrounding structures. These children often require an open reduction of the hip. The hip capsule is opened and all impediments to a reduction are removed. The child is then placed in a spica cast for approximately six weeks. Occasionally, reducing the hip places a lot of pressure on the femoral head. In this situation, the femur may be shortened by removing a small piece of bone. This relaxes the soft tissue around the hip.

A hip does not grow correctly unless the ball is in the socket. The longer the ball is out of the socket the worse the socket shape becomes from misdirected growth. The ability of the socket to reshape and correct itself slows with time. Greater deformation and slower correction speeds make delays in treatment troublesome.

As the child gets older still, the remodeling potential of the hip decreases absolutely, no longer just a question of slower speed. Children greater than eighteen months old often require additional osteotomies of the femur or pelvis to create a structure with enough stability to go the distance. And this then may or may not last into old age. Many of the adult hips with osteoarthritis that come to total hip replacement seem to be untreated degrees of early hip dysplasia.