Equinovarus is an odd description. Equino = "like a horse". To make sense of that you need to know that the horse hoof is a big toenail and that the

horse's back pointing joint is like our heel. So walking on toe is the equino part. Varus means that the part distal from the one named slants toward

body mid line. Much easier is "down and turned under". This is the posture of a club foot (left) which makes ground contact on the outer forward edge of the foot.

Equinovarus is an odd description. Equino = "like a horse". To make sense of that you need to know that the horse hoof is a big toenail and that the

horse's back pointing joint is like our heel. So walking on toe is the equino part. Varus means that the part distal from the one named slants toward

body mid line. Much easier is "down and turned under". This is the posture of a club foot (left) which makes ground contact on the outer forward edge of the foot.

In cerebral palsy, valgus (tilted so that the ankle bone, called the talus, falls inward and heel tilts out - or weight rests on

inner ankle bone) - valgus is far more common.

When the gastrocnemius or calf muscle (or Achilles) is tight, then the walking is on toe. But if the heel gets to the ground,

the ankle range may be insufficient to get it there. So the next joint down, the subtalar joint, beneath the talus, falls into valgus allowing the heel to reach the floor.

Occasionally, a muscle called the "one behind the tibia" or tibialis posterior, is also tight. If so, the subtalar joint cannot allow the heel to go outward (valgus) and instead is pulled inward (varus).

So?

Well, valgus is just another kind of flat foot. Bad valgus is bad flat footedness. Ehh. Comfort aside, from the point of walking, per se, it is not the end of the world. It may be the straw that breaks the camel's back when other factors undermine stability. We try to prevent valgus and use an assortment of in shoe or AFO braces to offset it.

But varus is a mean ornery and way underestimated trouble maker. We don't need great skills to compensate for valgus, but very few of us, maybe none of us, can effectively compensate for even small amounts of varus. Varus is very destabilizing.

Patients with varus do all sorts of weird stuff so as to not have to deal with it. They hop over the foot, or stick it way out to the side so as to land

on the "bottom" surface, or short step, or some combination.

Patients with varus do all sorts of weird stuff so as to not have to deal with it. They hop over the foot, or stick it way out to the side so as to land

on the "bottom" surface, or short step, or some combination.

In a sense, the way we compensate for a thumb tack in one shoe is about the way we compensate for varus. We avoid the noxious thing altogether.

Analysis of gait in folks with varus generates all sorts of apparent "abnormalities" which are red herrings (true and not causal).

Because it is so poorly compensated, it is also very

apt to cause tripping (instability) and the feet may carry one or more stress fractures.

Because it is so poorly compensated, it is also very

apt to cause tripping (instability) and the feet may carry one or more stress fractures.

Top view x-ray of foot: Note the talus and navicular bones (two sets of green arrows) badly offset as if the navicular were pulling off the talus.

The red arrows point out three different stress fractures in the metatarsals caused by mere walking.

|

This is so utterly true that we have witnessed on several occasions that when there is bilateral mild neurologic impairment, the bad side is always designated as the one with varus. Yet, after fixing the varus we find that the bad side may indeed have been the dominant side making the good side look like the real bad side.

Remember there is the problem thing and there is also the separate ability to compensate for the problem thing. Because varus has no good compensatory mechanism in the most skilled of us, the varus side will appear the worse of the two in question. Although mechanically it may be, neurologically it might not be so.

Now this comes up in a big way after selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR). The neurosurgeons do not want to impair bladder and bowel function when doing SDR and so they do not completely cover the full length of leg innervation with that process. The hips and knee functions may do splendidly but portions of the ankle motors may go untreated. Sometimes an ankle-foot varus results. That varus may be impossible for the patient to deal with whereas they were (absent varus) able to work around their spasticity. The result gets called a "failure" or a complication. Yet its isn't. Fix the varus and the improvement from the SDR becomes quite evident.

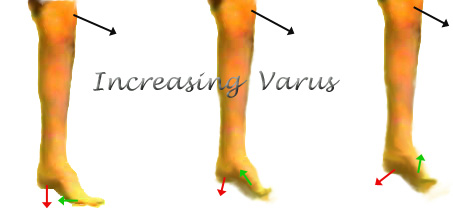

Varus comes in flavors. Doesn't everything? The foot may be down and turned under because the up and outward pullers are weak or denervated. Or, the foot may be down and under because the down and under muscles are nonstop and unmeasured (spastic etc.). Mild turning under also occurs when the foot is only strongly pulled down by the calf muscles. This is because the lower of the two ankle joints which steers outward at the upward extreme, steers the foot under at the lower extreme. So, occasionally, just fixing equinus will resolve that sort of mechanically induced varus. Percutaneous lengthenings are effective in this case.

When the down and under is from weakness or absence of an up and outward puller, only a brace or a muscle transfer will resolve it. Something has to do that job. There are may choices. Surgeons select from the inventory of what can be modified or spared for that job.

When the cause is unremitting down and under pulling from spastic down and under pullers, nothing works other than getting rid of the cause. Braces often fail as the skin just can't take the war that results from fighting this nonstop active cause. Botox might briefly help and even be used to allow a better brace to get the advantage, but seldom is that final. It merely buys time. Transferring the offending muscle to neutral ground is very effective and hugely habilitating because it removes the very debilitating varus.

Bilateral varus? Oy. One side is bad enough. Two sides removes any discussion. Fix it.

Diagnostics:

Jugular Lymphatic Obstruction Syndrome. Onset at birth.

|

There is another point to be stressed when discussing varus. How did it get there? Varus is never a normal finding. Varus may be seen along with cavus (arch makes a cave, a very deep or overly high arch). Nearly always, there has to be some sort of consideration as to what is causing the cavo-varus foot. It could be polio, any of a long list of genetic or hereditable syndromes (especially those associated with ataxia - imbalanced or reeling stance), or those from neuropathies and the like.

The orthopedic reason for knowing is that if you are going to fix it, you need to know whether the parts used to fix it will last or eventually become part of the process. Who exactly pursues this diagnosis varies with where you live. In some hospitals it is the neuro-geneticist, or geneticist. In other places physiatrists, neurologists, or developmental medicine practitioners supervise this process of evaluation. Some syndromes manifest right at birth and some may take many years to reveal themselves.